International Women’s Day

The fact that women can study at universities, vote or work has not always been the case in Slovakia. Even after 1900, there were strong tendencies to tie a woman to the stove, and in the movement for women’s equality and feminism, some peoples saw the worst that could be. Fortunately, they failed to do so and the women won their fight for equality. Since 1910 , they have always had their international day on 8 March. It belongs to the memory of those who did not give up the fight for equality and ultimately won it.

We are in Hungary, in the second half of the 19th century, when women do not bloom very much. They are still at home in the role of mothers and guardians of the family heat – they give birth, embroider, cook, work in the field, preserve, plant and bake, take care of children and cleanliness in the house. They are lower-educated housewives who are totally dependent on husbands. The ambitions that exceeded their role were perceived as damaging in society.

Around 1860, girls were educated partly in different subjects from boys in Hungary – for example, in higher education, girls were not taught the basics of agriculture, national law or the basis of accounting, geometry. A partial improvement occurred with the new Education Act (1868), which finally introduced a truly compulsory school attendance “for children” – i.e. girls and boys between 6 and 12 years and 15 years of age and set penalties in case of neglect. He allowed girls to study at higher and bourgeoske schools. In 1875, the first higher girls’ school was established in Pest and in 1896 it was joined by the first grammar school for girls. However, their aim was also to admes women, so women’s organisations in Hungary also concentrated heavily on women being able to study in the Slovak language. Since 1895, they have even started recruiting ladies for university studies of pharmaceutical, philosophical and medical fields of study.

“Fortunately, some women have been further admesed by the criticism of society and confirmed that they are doing the right thing. So they begin to agitate and gradually penetrate public life. In literature there are reflections, short stories and novels of Elena Marótha – Šoltésová, Hana Gregorová, Theresa Vansová. And their heroines literally do wonders with young Slovaks of the time ….,” explains SNK Ceo Katarína Krištofová. She adds that although they are mothers, they are also loving and beloved wives in a happy relationship, educated and equal to their husband. Or are they self-existing women who would rather be alone than living with someone without love…

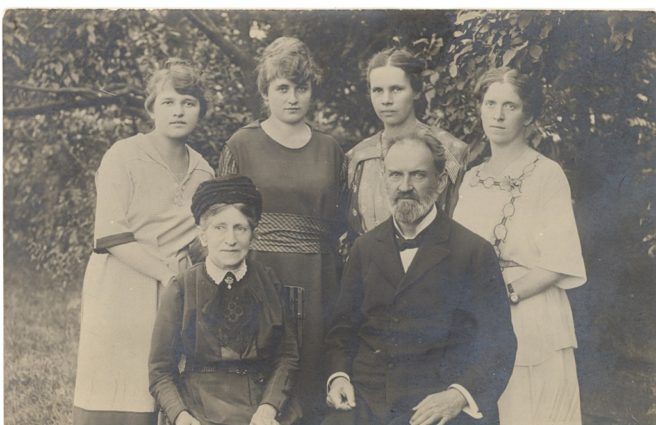

First teacher’s team, girl. Schools “Živeny” in T. St. Martin in 1919. /In the picture sitting: E.M. Šoltésová

and Fr. Mareš. Standing: Dr. A. Hornek’s exom. Bobková, Zlochová, Dr. Štechová/

(Literary archive of SNK, sign. PM 15/713)

Committee of the Živena Association in 1933 with pupils of the Institute of M.R.Štefánik in front of the building. /Seated: E. Hroboňová, A. Čajdová, Elza Vančová, E.M. Šoltésová, Fr. Mareš, A. Halašová and others. Photo: Horník, A., Martin (Literary Archive of SNK, sign. PM 15/716)

ELENA MARÓTHY – ŠOLTÉSOVÁ

Her maiden and female characters were wise, brave and conscious – as wives in a happy and idyllic marriage, they were able to encourage their husband to achieve higher goals with their love and activity. Šoltés herself is also keen to put an end to the title of women “grasce lady” and held the title of “mistress” and exom, not the use of “they”. The daughter of parish priest and writer Daniel Maróthy, she is a very receptive child, but in some ways no one has sympathy for her desire to learn. Her fate was sealed by marriage of reason and she moved to Martin, the centre of culture, with businessman Ľudovít Šoltés. She survived the deaths of her children and husband here, setting up schools and magazines for girls and women. “It’s an embarrassing sign of our great backwardness that we still have to blame for women’s education. Jesti for people at all education is desirable, well, it is understood, it needs to be male and female. Elsewhere, the question no longer arises because its need is widely recognised,” she writes in the article Need for Education for Women.

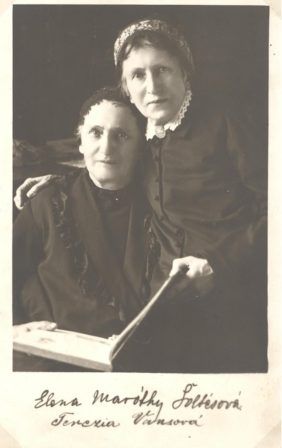

Theresa Vans (left) with Elena Maróthy-Šoltésová. Photo: Otto Lechnitzky, Banská Bystrica

(Literary archive of SNK, sign. As of 18a/7)

In correspondence with his girlfriend and the headteacher of the town school in Kromeříži, Antónia Gebauer, they discuss girls’ education. She offers Šoltésová qualified teachers and suggestions for focusing also on the filling of girls’ schools that have already operated in the Czech Republic. It sends her syllabus for women’s schools “průmysly and kursy housewives” and, from her own observations, advises, that girls should specialize in a particular field of work after 14 years of life: “It is up to the man to recognize the woman capable and to call her to work together in a whole,” Gebauer writes in a 1919 letter to Šoltés, adding that she was hurting. that Slovakia is not represented by a woman in the National Assembly of Czechoslovakia.

AMBRO PIETOR

However, in order not to be unfair, some men have also adopted progressive ideas from abroad – Ambro Pietor was a shining example. As early as 1869, he wrote in the National Announcer that “A woman’s gender is mistaken for enlightening, this is to give way to a hung moral life” and sees the cause in “a partisan world male, any reigning, because he bears the greatest blame.” In the newspaper, he called on the Slovak public to set up the Women’s Association Živena (4 August 1869 in Turčiannský St. Martin), which would aim to educate Slovak women. The Association started outreach work, published women’s magazines and made a proposal three times to set up educational girls’ institute in the Slovak language. However, the Hungarian Government rejected this. It was not until 18 November 1919 that the first Slovak higher education institution for women’s professions and, in addition, the five-month-old school housekeeper in Martin accepted its first pupils. In 1921 there were already 30 trade unions in Czechoslovakia, 10 girls’ schools and more. Female staff and instructors were trained. They learned to cook, sew, manage education and domestic economy, learn how to perform hygiene of themselves and the child. They obtained valuable information about in which professions they could also apply about the possibilities of setting up small production at home. The elements even managed to set up crèches for working women – the first opened on 28 October 1922 in Martin and for a long time they were the only ones. In 1926, the first Slovak doctor – MUDr. Mária Bellová, daughter of an evangelical parish priest from Liptovský St. Peter – graduated from pest university.

Maria Bellová at work on the front in 1916, author of photography: Szilágy Somlyó, Oradea.

(Literary archive of SNK, sign. SB 13/53)

SVETOZÁR HURBAN – VAJANSKÝ

Unlike Pietra, S. Hurban – Vajanský was strictly conservative and feminism was called “a piece of the most ugly and edible thing of the 19th century, i.e. a piece of feminism… When he (a woman) throws up on a man as he climbs the grandstand, then he throws away all these virtues and remains – babizeň.” – he writes in the National Newspaper in 1904. And in a second breath, he adds, “making bread counter to a woman’s calling and playing a stand-up – behold, dear theatrical – deprives a woman of femininity and, for the most part, morality.” What would S. Hurban’s mother – Vajanský – Anička Hurbanová – Jurkovičová say about such a statement?