The National Széchényi Library stores hundreds of millions of pages of documents. At present, we digitise 1 to 1.1 million pages every month, which is quite significant even at an international level. According to the plans, we digitise journals, books, and special documents, as well as codices, sheet music. When the digitisation center was established, we did not have the right workflow to meet our objectives, so we had to reorganize our work procedures completely. We managed to multiply our skills with basically the same staff, with training and retraining, and last year, we were able to start mass-producing digital documents at our library.

Imagine an area of over a thousand square meters with robotic scanners and V-shaped book scanners, which are used to digitise sensitive documents. The workflow is more complex here than at for-profit companies, since we need to preserve the original documents as well.

The goal is to make all Hungarian printed matter available online.

The very first Internet archives appeared after the turn of the millennium, managed by national libraries in more than 50 countries. It is impossible to archive every status of every website, or every new news item on a news website. The established method is that each country preserves its own web space, so we save the .hu web domain and all Hungarian-related sites beyond the borders twice a year. We have a robot run through the .hu web space, down to a certain depth, saving the state of the page at that moment. In the case of some major events, such as the 2021 International Eucharistic Congress, the Olympics, and the UEFA Euro championship, we preserve every single news article and web content. This is referred to as event-based web archiving.

We are already processing digitisation of all publications in the public domain, which means works of authors which passed away more than 70 years ago or works for which a given institution has permission to make accessible. There is an intermediate area: EU copyright law now allows publications that are no longer commercially available but are still protected by copyright to be made available as part of the public domain after they have been “parked” in the EU database for six months, with the provision that the author or the heir can remove them at any time. Our goal is not only to digitise as much of our cultural heritage as possible but to make it available, either online or on a network dedicated to this purpose.

Will there be any need for a library? I imagine there will. Perhaps they will not be located in buildings, or perhaps not in buildings of this size, but there will always be a need for people who can help guide us through the flood of information.

If we cannot understand the library as something more than a collection of printed books, this would mean that we consider the library as an institution to be little more than a warehouse. But a library is much more than that. Libraries mean books, but they also mean qualified professionals, that is, librarians, not to mention readers. The digitised content online with all the metadata is hardly a sufficient substitute or replacement for a library. Libraries are places that provide reliable, credible information, places where culture and literacy are nurtured, encouraged, and facilitated by qualified staff. Libraries have been around for thousands of years – in various forms, using various media – and I believe they will be around for many more decades and centuries to come.

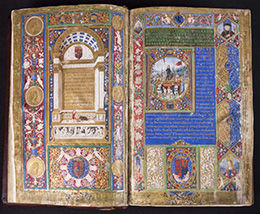

In addition to books, periodicals are another huge and frequently used part of the collection, but half of our documents are, in fact, posters and small print. The latter come in an infinite variety of forms, such as business cards, program guides, menu cards, invitations, stamps, or obituaries. We have a large collection of gramophone records and photographs. and The library contains manuscripts from the library of Hungarian king Mátyás Hunyadi, as well as seven hundred codices, mostly in Latin but also in Slavonic, German, and Greek, and one or two codices written entirely in Hungarian. There are more than 1,500 historical interviews to choose from. The library is practically an inexhaustible resource.

In addition to books, periodicals are another huge and frequently used part of the collection, but half of our documents are, in fact, posters and small print. The latter come in an infinite variety of forms, such as business cards, program guides, menu cards, invitations, stamps, or obituaries. We have a large collection of gramophone records and photographs. and The library contains manuscripts from the library of Hungarian king Mátyás Hunyadi, as well as seven hundred codices, mostly in Latin but also in Slavonic, German, and Greek, and one or two codices written entirely in Hungarian. There are more than 1,500 historical interviews to choose from. The library is practically an inexhaustible resource.

Our oldest items are two papyrus fragments, over three thousand years old. On the other hand, some documents that were written or printed on paper used during wartime, for example, or acidic, poor-quality materials have a much lower chance of survival than an 800-year-old codex, not to mention today’s low-quality paperback editions or books bound using glue. To survive for hundreds or thousands of years, books need continuous preservation work, done by our conservators. In an ideal case, several generations will be able to admire the library’s holdings. A common problem with manuscripts is that they were written using unsuitable inks or have been exposed to forces (light, temperature, etc.) that affect their condition and their future.

We are constantly searching for new technologies that help the long-term preservation of data and digital objects. As early as the 2000s, a seed bank was established in Svalbard, preserving a huge proportion of the seeds of the world in permafrost. In a similar way, an archive was set up a few years ago along the same lines. It is used to store film copies of the digitised material from each major library in permafrost. The National Széchényi Library was one of the first national institutions and the first national library worldwide to join this endeavor. We have recorded digitised versions of the manuscripts from the library of Mátyás Hunyadi, Count Széchényi’s map collection, as well as posters from the 1920s and 1930s on special tapes. This is another way of ensuring long-term preservation. Experiments indicate that the film reels can be preserved for a thousand years, at least, in the ice cave.

Source: special issue of the journal Magyar Kultúra, titled “Books” (2023/5).